| Разделы | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| @ Иллюстрации и Обложки | |||||||||||||||||||||

@ Книги

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| @ Планета Перн | |||||||||||||||||||||

| @ Драконы и файры | |||||||||||||||||||||

| @ Дельфины | |||||||||||||||||||||

| @ Биология | |||||||||||||||||||||

| @ Общество | |||||||||||||||||||||

| @ Родословные | |||||||||||||||||||||

| @ События | |||||||||||||||||||||

| @ Энциклопедия | |||||||||||||||||||||

| @ Улыбнитесь | |||||||||||||||||||||

| @ Гостевая книга | |||||||||||||||||||||

| last modified

19.02.2005

|

|---|

Всадники Перна. Материалы

The Dragonlovers guide to pern

II. Fit for Human Habitation

THE EEC EXPLORATION

In order to designate a planet as a potential site for colonization, the Exploration and Evaluation Corps was required to locate at least five identifiable landing sites, potable water, breathable air devoid of methanes or cyanides, and ensure that no sentient life form already existed there. The Rukbat system was at the extreme reach of the exploration circuit, but it seemed promising.

The EEC team that discovered the system consisted of four men and women. Ben Turnien was a top-flight geologist and chemist. Captain Castor, the pilot, was also an accomplished chemist. Shavva bint Faroud, a biologist, shared the duties of nexialist with botanist Mo Tan Liu. Unfortunately, the team was short-handed; they had lost four of their original eight to ill luck and carelessness on planets visited earlier, and Castor was unable to join the landing party due to a broken ankle.

The remaining three were forced to double up on jobs planetside. Even allowing five days for the survey, the small team was unable to give the world more than a cursory examination.

They found the third planet circling Rukbat to have a breathable atmosphere with slightly above normal oxygen content, and gravity only ninety percent of Earth normal. Through the atmosphere, the star Rukbat shone golden with a cast of green. The planet's soil appeared to be arable, fostering plant growth that, although its green hue tended to range more toward blue or yellow than did that of Earth vegetation, appeared to utilize photosynthesis to live.

Fossils showed animal life to have existed on the third planet as early as 100 million planetary years before. The most interesting casts were of a large creature with four limbs and two wings, big lizardlike creatures, and some gigantic snakes taken from a site north of the body of water on the southern continent that would one day be called Drakes Lake, At the thirty-five-million-year mark, widespread evidence of tree-fern fossils suggested a carboniferous landscape.

An extensive tar pit revealed fifty-thousand-year-old fossils of ruminants, flat-toothed cattlelike creatures that ate only vegetation. The “grass” those extinct creatures chewed contained no silicates and was visibly triangular in cross section, like most of the modern vegetation. The ruminants appeared to be extinct, which bothered the exploration team but, in fact, eased the way for a potential colony to bring in its own herbivorous meat animals.

More fossils, this time in a core sample taken offshore, showed a marine shell-colony system similar to coral that had existed for some 500 million years.

Life on the planet—marine, plant, animal, and fungoid—displayed considerable variation, suggesting to the landing party that the process of evolution was ongoing here, and not stagnant. The nexialist Liu reported finding literal fungi that showed visible independent movement. Only one unexplained phenomenon was discovered: a large number of circular bare patches scattered all over the planet's surface. The team assumed a local fungus or vegetable plague was to blame, although they had no idea why the strong winds would not have reseeded those spots.

The mycota that proved to be the most interesting to the botanist/nexialist Liu was first discovered in a cave on the biggest island. He identified the luminous fungus as a mycelium that glowed when exposed to oxygen. It retained its light for an unusually long time, suggesting its usefulness as a light source. The spores were tiny, but there were enormous quantities in the caves.

Specimens were taken of seaweeds, trees, grassoids, beach-walking insectoids and crustacepoids, red and green algae, and of the soil itself. Ferns grew in abundance in the tropical regions of the

planet. Flying insectoid pollinators attracted to flame had double sets of wings. Reptiloids, some as big as seven meters long and ten centimeters thick, inhabited the jungles. Big six-limbed avians

which resembled English river barges, or “wherries,” were named for them in the EEC report. Two identifiable types of the “wherry” avians, both predatory, were cataloged, as were numerous

brilliantly plumed smaller avians.

Specimens were taken of seaweeds, trees, grassoids, beach-walking insectoids and crustacepoids, red and green algae, and of the soil itself. Ferns grew in abundance in the tropical regions of the

planet. Flying insectoid pollinators attracted to flame had double sets of wings. Reptiloids, some as big as seven meters long and ten centimeters thick, inhabited the jungles. Big six-limbed avians

which resembled English river barges, or “wherries,” were named for them in the EEC report. Two identifiable types of the “wherry” avians, both predatory, were cataloged, as were numerous

brilliantly plumed smaller avians.

A thousand types of the local insectoids, inland, shoregoing, and seagoing, were identified and cataloged. A brief survey uncovered 150 kinds of bacteria, fungi, and mycorrhizae within a fairly small area. Of the lower chordata, nematoda, “earthworms,” sandworms, and ground mites abounded. Tunneling creatures that the team believed were not reptiloid managed to avoid the team's snares and had to be implied in the landing report. Fish and larger creatures fed along the shores at planetary dusk.

Large herpetoids existed in the jungles and in the warmer mixed terrain. One mottled monster seven centimeters broad and five high, with tentacles and claws and no discernable eyes or mouth, was described by Shavva in the report. The creature lured its prey with a terrible stench, an odor unpalatable to the human landing team but no doubt attractive to its food, and trapped the victims on its sticky back. One of the scientists suggested that the sticky back was an external digestive system.

This creature led them to the discovery of another plant, a spine-throwing bush that shot its barrage toward anything that touched it.

Flying creatures with hides of green, blue, brown, bronze, or gold, four limbs, wings, heads, and forked tails, were spotted, and the landing party suspected them to be the egg layers who produced the shells lying in the beach sands along every tropical coast. The fliers were considered to be at least potentially intelligent, though limited. If the creatures laid their eggs on shorelines close enough to be washed away during storms, the team felt that they lacked reasoning capacity. And yet they were capable of organized play, which suggested they were aware of their environment. No more was noted about those graceful creatures in the report.

The planet was rich in minerals, though ore, which existed in quantities too small to be of interest to the Federated Sentient Planets as a mining concern, was not easily accessible. Near a small chain of lakes in the Southern Continent west of a vast lake feeding three rivers, investigation revealed deposits of iron, copper, vanadium, platinum, and gold. More minerals, including tin, bauxite, and nickel, were found farther to the west in dense, sulfurous mud flats. Gem-quality minerals existed in plenty, including diamonds, rubies, quartzes, beryls, and an entire range of precious stones. Three landing sites were identified in the South.

The big islands in the bay to the north were largely basaltic. The largest was a puzzle of geological samples. The western half was limestone overlying schist,

with granite outcropping on the southwest coast. Gold-bearing quartz and all the corundum minerals appeared on that island, as well as black diamond crystals. The sites produced enormous high-quality rough jewels, some of which were taken back by the landing team for further study.

The big islands in the bay to the north were largely basaltic. The largest was a puzzle of geological samples. The western half was limestone overlying schist,

with granite outcropping on the southwest coast. Gold-bearing quartz and all the corundum minerals appeared on that island, as well as black diamond crystals. The sites produced enormous high-quality rough jewels, some of which were taken back by the landing team for further study.

Two potential landing sites were identified on the Northern Continent. One lay at the top of a chain of small lakes near what would one day be Telgar Hold. The other lay at the source of the river flowing near what is now Benden Weyr.

A hearty plant with delicious pungent-smelling bark passed the scientists' toxicity test. An infusion of the bark proved to taste as good as it smelled, like a

cross between coffee and chocolate with a spicy aftertaste. To produce a strong enough infusion to drink, they ground up some of the bark and brewed it like coffee. In time, both the tree and the

drink came to be known as klah.

|

COLONIAL LANDING, THE SHIPS AND COMMANDERS

A Charter was drawn up between the group of colonists and the Council of the Federated Sentient Planets. Six thousand twenty-three people signed the Pern Charter, giving them rights to certain numbers of stake acres. Three ships, under the command of Admiral Paul Benden, a hero of the Nathi War, spent fifteen years crossing from Earth to the Rukbat system. The Yokohama held the same number of people, both awake and in deepsleep, as the Buenos Aires and the smaller Bahrain combined.

|

One more sentient life-form joined the humans' exodus to Pern: Twenty-five dolphins, all volunteers, slept in the cryogenic chambers. Like the humans, they were eager to explore new seas, and they had no objection to be put to work rounding up specimens of native creatures for the human marine biologists.

Each ship was constructed on long metal vanes interposed between the engines at the rear and a spherical living-and-cargo pod at the forward end. Cargo that did not need atmosphere or special care was lashed between the vanes to save interior space. Access to the engines was through a narrow passage that led through the core of the vanes but could be shut off from atmosphere.

The journey took fifteen Earth years. The crew aboard each ship alternated five-year shifts out of cryogenic sleep. Only vital personnel, among them Admiral Paul Benden and his two captains, Ezra Keroon and James Tillek, along with astrogator Avril Bitra, spent the entire trip awake. Benden had been the commander of the Purple Sector Fleet and led the FSP victory at Cygnus, which turned the tide of war against the Nathis. He was in his eighth decade when the colonists departed Earth. Humans of his day could expect to live up to eleven decades, so he was considered to be in late middle age.

Six months before they reached Pern, the landing specialists were awakened to give them time to adjust before their services were needed. Emily Boll, co-leader of the colony, began final organization of the first landing personnel. The ships entered Pern's system at the end of the winter season in the Southern Continent, late autumn in the North.

Charter members of the colony, mostly veterans or surviving dependents of parents killed in the Nathi War, were allowed to purchase “stake” acres on Pern.

Specialists could buy stake acres, too, by contracting their services, so many acres per contract year. There were approximately the same number of specialists as charterers. The third group was made

up of 721 nomads—Jensche, Tuareg, gypsies, and Irish traveling folk—who, having resisted every assimilation or indoctrination program of Earths increasingly high-tech society, were no longer welcome on their home planet. Taking the nomads along to Pern had been a requisite of the FSP-colonist Charter. All the two

groups had in common was the wish to escape the over-technicized, impersonal society of the FSP worlds or the memory-filled remains of the war.

The chosen landing site, named Landing, was on the volcanic plateau in the South-ern Continent behind an extinct cone of enormous size with three small cones in a line pointing away from it to the southwest. The large volcano was named Mount Garben, in honor of a senator who had been of service in expediting the FSP's approval of the colony.

After all the cargo had been brought down, the two smaller ships were completely gutted. Everything usable was taken, from bolts to the fuel tanks strapped alongside the cargo bulk. In time, the Yokohama was the only ship with functional machinery left aboard. The communications receiver and the voice-activated computer which had guided the ships to Pern were not taken down to the surface. Nothing was left of the Dawn Sisters, as the orbiting ships came to be called in later centuries, but the spheres and vanes.

NATIVE FLORA, NATIVE FAUNA

The leaves of the local flora were predominantly acuminate or ovate at the apexes, and many had sagittate, truncate, or ovate bases, giving them the

appearance of arrowheads or dragon-tails. Pernese leaves were angular and sharp, unlike most Terran plants, which had rounder outlines.

The leaves of the local flora were predominantly acuminate or ovate at the apexes, and many had sagittate, truncate, or ovate bases, giving them the

appearance of arrowheads or dragon-tails. Pernese leaves were angular and sharp, unlike most Terran plants, which had rounder outlines.

On Pern, shrubs grew in plenty, but there were disturbingly few old trees. All those discovered by the colonists seemed to be no older than two to four hundred years. The nonforested areas or plains were covered by the blue-green triangular grassoid described by the EEC team. This proved to be heavy in boron as well as containing the expected trace minerals of copper, magnesium, and sodium, but curiously, no silicates. The internal bacteria in Earth herd animals would need to be adapted to process native vegetation.

In the marshy lands thick-stemmed brushes the size and color of sage plants were discovered. Their arrowhead-shaped leaves, bruised and rubbed on injuries, provided relief from pain. Another native plant, with sharp spearhead leaves, proved to have a narcotic sap, which the physicians studied for future use.

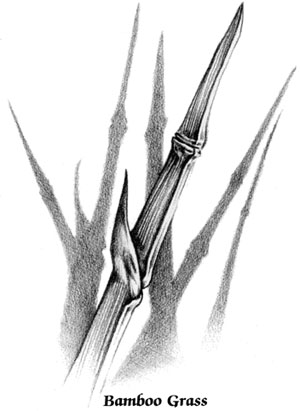

Weavers found native flax and sisals among the fibrous plants brought in by the searchers. Some textile makers experimented with weaving thread made of a pounded fiber produced from the inner sheath of a triangular native bamboo grass.

As the plant life was new to the FSP-trained botanists, they created their own names for the local plants. Among the first to be named were the sungazers, the flowers of a little plant that grew mostly underground, showing just the bloom in the grass, very much like an Earth strawflower or windflower.

The rain forests around the Landing plateau appeared to behave very much like those on Earth. The first plants, such as the local bamboo, grew up very quickly,

then died and rotted to provide humus for the next generation of trees, creepers, and grasses. In general, the greenery was much thicker than the colonists had cause to expect from the report of the original

exploratory team which had visited this world only twenty years after the rogue planet had passed by.

Parasites

were rife. Pern had numerous types of insects, most of which had been noted in the EEC report. Buzzing flies, fireflies, and some types which the entymologists called VTOLS (for “Vertical Take-Off and Landing”) were caught in large numbers around the settlement. Stinging pests like bedbugs and “crawlies”—tiny creatures like

six-legged geckos with suction cup feet quickly started making nuisances of themselves in the humans' new habitations. “Rollers” were a type of wood louse. “Springs” were insects that

hung in spiral loops until they found something or someone to cling to; their irritating, prickly bite had to be treated with an antihistamine cream. Millipedes and flat, segmented worms scavenged among the seaweed or fallen leaves in the forests. There were also sandworms and earthworms, two related species of

burrowers that the botanists observed filling the same niche as the Terran worm.

Parasites

were rife. Pern had numerous types of insects, most of which had been noted in the EEC report. Buzzing flies, fireflies, and some types which the entymologists called VTOLS (for “Vertical Take-Off and Landing”) were caught in large numbers around the settlement. Stinging pests like bedbugs and “crawlies”—tiny creatures like

six-legged geckos with suction cup feet quickly started making nuisances of themselves in the humans' new habitations. “Rollers” were a type of wood louse. “Springs” were insects that

hung in spiral loops until they found something or someone to cling to; their irritating, prickly bite had to be treated with an antihistamine cream. Millipedes and flat, segmented worms scavenged among the seaweed or fallen leaves in the forests. There were also sandworms and earthworms, two related species of

burrowers that the botanists observed filling the same niche as the Terran worm.

The biologists found flying pollinators that warred with their imported bees (and won), but the most active pollinator was the trundlebug. It was found to eat parasites, as well as to carry pollen and turn the soil, combining in one creature bee, earthworm, and ladybug. The botanists encouraged it to frequent the new Earth crops. Trundlebugs had the most elaborate color camouflage of all the insects; varieties of black, brown, sand, blue-green, and crystal-clear were found.

All noninsectoid fauna on Pern was warm-blooded and based on a boron-silicon system, rather than the iron-calcium bond of earth animals.

Snakes with turtlelike faces existed in the jungles. Most of these were poisonous and left track marks from the toe teeth along their length on those creatures unlucky enough to be caught in their coils. Similar snakes that grew up to elephantine size lived in the rivers and seas.

The so-called tunnel snakes, which actually had legs, were the most numerous pests, appearing in caves and stony outcrop-pings. There were numerous varieties of the six-limbed beast. Most averaged two to four feet in length. Some had scales; some had skin. One type had very long legs, but most of them had short, stubby limbs for creeping low against the ground. Many varieties of tunnel snakes had sharp, powerful front claws for gripping and rending. The rear legs pushed the tunnel snakes' skinny bodies through the smallest openings in the rock. The middle pair of limbs served as stabilizers in land-bound varieties and as pseudoflippers with vestigial claws in those species that were water dwellers.

Most tunnel snakes had hearing organs in their chests, close to the ground, but there existed one variety of deep-tunnel beast that had no less than six ear-spots, to make up for the fact that it was nearly blind.

The water-dwelling tunnel snake's bite was venomous and could be dangerous if not treated promptly. The flesh of a victim would swell up painfully. All tunnel snakes had the ungulate jaw that allowed them to ingest small creatures whole. They could go for long periods without feeding, which helped them survive during Threadfall. Some hibernated during the cold seasons when prey was scarce.

Packtails, a tasty but dangerously barbed fish, resembled Terran monkfish. Fingertails, also edible, were a small carplike fish with a whippy tail. Spider claws resembled crabs with many pairs of jointed legs.

The first colonists trapped wherries as a source of meat. These predatory avians were the major hunter/scavengers on the planet and killed large numbers of the smaller imported animals during the first months of settlement.

Wherries had no feathers. Their bodies were covered with thick proto-feathers, multiple tufts like marabou. Their wings were cartilaginous and membranous under the thick down. Like the other native animals of Pern, wherries had six limbs: two wings, two front feet, and two back feet. The front feet, which were much smaller than the back two, had one mobile claw that locked into two rigid claws like pincers, which were used to grab and rend. The back legs were well-muscled and could be employed to kick powerfully, as well as to help the bird leap into the air. Their three toes canted backward when they flew, to keep from being caught by animals on the ground or other wherries. The big avians turned cannibal when one of their numbers was wounded or killed.

Wherries nested in caves or rocky out-croppings, much as Earth seabirds do. They ate fish, carrion, tunnel snakes, insects, offal, or garbage.

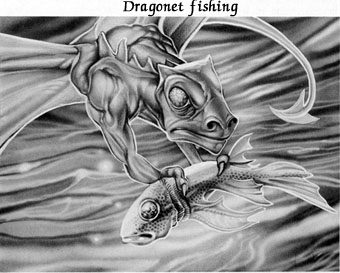

DRAGONETS

The “graceful flying creatures” of the EEC report were spotted first by children out searching for biological specimens. Through luck and good timing, the children discovered that the creatures' hatchlings would, not unlike Terran ducklings, Impress on the first being that fed them, human or dragonet. Soon many of the colonists had bonded with baby dragonets.

The dragonets were self-sufficient. They could fly almost from the moment of hatching, and they hunted for themselves after accepting the first meal offered by the impressor.

A fair of dragonets would begin humming when a hatching was imminent (and experience proved that the creatures could predict human and animal births, as well).

They surrounded the eggs with a ring of seaweed and filled it with small fish and crawling creatures that would provide the hatchlings with their first meal. As soon as the newborns broke shell, they

were greeted with cries of joy and offered food. A hatch-ling had a fierce birth hunger, and the first being—dragonet, human, or otherwise— that offered it food would Impress it.

IMPORTED FLORA

The botanist raised seedlings of all Earth trees in the hydroponics labs. The

gingko and cottonwood trees did well in the open plains, breaking the ground and

providing shelter for the oak and pine seedlings planted in their shade. Ash, rowan, and scrub pine went into the higher reaches, and willow trees grew on the wet riverbanks.

The botanist raised seedlings of all Earth trees in the hydroponics labs. The

gingko and cottonwood trees did well in the open plains, breaking the ground and

providing shelter for the oak and pine seedlings planted in their shade. Ash, rowan, and scrub pine went into the higher reaches, and willow trees grew on the wet riverbanks.

Earth-type grass was adapted for the animals to eat until they were sufficiently used to Pernese grassoid. In the Ninth Pass, isolated patches of grass still survive on the Southern Continent. Many types of Earth and First Centauri trees reseeded themselves on grubbed ground and can still be found scattered among the Pernese types.

All of the types of Terran grains and legumes did well in the rich native soil. The first crops planted were fodder for the newly bred herds of imported grazers. Packaged organisms that would react symbiotically with the local bacteria were introduced to the soil to make native grasses palatable to the imported animals. The concentrations of boron, rendered inactive, simply passed through their digestive systems.

Mushrooms were raised by the colonists side by side with edible native fungi in the caves that riddled the palisade overlooking the Jordan River. Apples, pears, wine grapes, and numerous other fruits adapted easily to the Pernese soil.

All the medicinal and cooking herbs, among them tarragon, rosemary, lovage (for coughs), borage, thyme, coriander, nutmegoid bark from First Centauri (Earth nutmeg did not translate well), willow for headaches, and hazel for the skin, were grown from seed drawn from the agronomy stores, and thrived in Pernese soil.

Though treats were rare as the supplies began to dwindle, the bakers created little hand-sized one-crust pies for the children from bits of sweet dough and berries, as the brambles matured. Survivor species such as blueberries (which make the most popular bubblies), blackberries, raspberries, and gooseberries still exist in the Present Pass.

It was a spacer tradition to begin distilling liquor as soon as possible when reaching a new planet. It became the measure of every holder or each expedition

to make “quickal” almost immediately. The administration trusted the colonists not to use plants that had not been checked for toxicity, but those fruits that had tested safe went promptly into

the stills. Some of the imported fruits had a very high sugar content and made enormously powerful quickal. The local fruit made potable drinks, and everyone traded crocks of his or her particular brew.

IMPORTED FAUNA

The stores of ova and sperm aboard the ships were extensive. Any variety of any species that the biogeneticists had thought would prosper on the new world was included. Animal host mothers, some cows and goats of small but sturdy genotypes, were shipped frozen from Earth to Pern and revived to bear fertilized ova of nearly all the larger animals brought from the Animal Reproduction Banks of Terra.

The bearing techniques had been perfected on First Centauri. A host mother did not need to be of the same species as the fetuses she bore. With help, a goat could carry and bear calves or lambs, and a cow was capable of bringing colts and young llamas to term as easily as it could bear its own calves. The cattle of choice were long-haired Scotch cattle with short, curled horns, a small but very tough breed. Ova implanted in them were of every type of cattle suitable for milk, meat, or hide. The sheep were of various kinds, both long- and short-fleeced. With the exception of the Kashmir, all the goats bred survived.

Strong but fairly small horses were bred, blending Connemara and Welsh strains for riding. Shire horses were bred as draft animals and for the gypsy wagons. Llamas served as beasts of burden and to provide hair for spinning.

Pigs were genetically adapted

for survival on Pern

The pigs were useful as disposal systems, transforming slops into protein-rich meat. Since not as many pigs were bred as other herd animals, pork came to be regarded as a special treat.

The chosen breed of dog was a ferret-dog, a Jack Russell terrier type that would kill the snakes that were attacking the nomad folk who slept in the open air. Later, the dogs were employed to chase and kill tunnel snakes. Felines were also useful against the vermin. Tabby cats were thawed out and began to produce litters within weeks.

Dogs were bred from original genetic stock

The first Earth creature to be born on Pern were chickens. Geese and ducks were next to be hatched out. The fertilized turkey ova failed to mature, but the other types of barnyard fowl were doing well enough that the veterinarians were not displeased to have lost only one species. Doves and pigeons hatched out, but between the wherries and tunnel snakes, neither species lasted long enough to mate.

Chickens and geese exist on modern-day Pern only in the warmest Holds and in batteries where they are protected from wherries. Very few ducks have survived to the present.

Spiders were successfully hatched out to kill parasites that invaded the human habitations. Spiders survive in the Present Pass but are now known as “gossamer spinners.” Ladybugs and other insects brought along to help propagate crops were mostly eaten by the much more numerous indigenous insect population, and few survive.

ADAPTATIONS

Permission had been obtained by the bioengineers to use the techniques of the Eridani to adapt animals to Pern. The most important of these methods were gene paring, mentasynth, and chromosome enhancements.

Fish and other marine life from Earth were introduced to the waters of Pern with a minimum of adaptational changes. There was protein-rich plankton in the seas, and the many indigenous fish were pronounced edible by the mariners and their dolphins.

Horses were improved somewhat by genetic tinkering. A number of genotypes coexisted and interbred for sixteen hundreds years, until the plague. During the plague all of the remaining true horses died out, leaving only the “runnerbeasts.”

The “grubs,” which rendered a piece of protected ground inimical to Thread, were engineered by a renegade biologist/botanist of the original colony. Unfortunately, he left no records of the research that generated these useful insects. He calculated that it would take four hundred years—or until the middle of the Second Interval—for the grubs to multiply enough to protect all of the Southern Continent. Twenty-five hundred years after Landing, the Southern Continent had become unchecked jungle because of the grubs' protection.

Forests of adaptable trees were grown during the Intervals from seeds saved in vacuum packs and cryogenic flasks. They had to be protected during the Falls, so only those species that would continue to be useful to humans were consciously preserved. Any sports that remained in the Southern Continent after the First and Second Passes managed to avoid being destroyed by Thread until the grubs had spread.

The creator of the grubs also experimented with cheetah fetuses, trying to produce a mentasynth-enhanced feline that would kill tunnel snakes and other dangerous creatures. He was familiar enough with the Eridani equations to know that cats reacted poorly to mentasynth, but he recklessly ignored that knowledge. His bioengineered animals killed him and escaped before he could call for help. They bred in the wild, unseen by man until the Sixth Pass.

When the population moved to the Northern Continent, herds of dogs, goats, sheep, and cattle were left behind to go wild. Some of the dogs and goats still thrive in the wild, but the other breeds have been wiped out by predators.

THE FIRST STAKEHOLDS

Stores were made available by requisition to all who needed them, ostensibly for the purpose of working toward the day when they would claim their stake acres somewhere on Pern and become independent and self-reliant. Each colonist, adult and child alike, understood that when the supplies were gone, they were gone, but until then everyone had an equal claim to the goods. There would be no monetary system instituted.

The colony administration treated all the people like adults, assuming that they would rely upon good sense and maturity to settle matters. Each man, woman,

and child was expected to accept responsibility for his or her own actions, and not fall back on a deity to solve problems—an outlook that was side effect of the crippling Nathi war. Hysterical

religions had been debunked. To the colonists, heroes were better than gods. Strong role models of both sexes were encouraged.

Within a year the colonists had spread to their chosen homes. As the planet had no sentient species, the settlers had the privilege of naming the landmarks and provinces of their new home. Some of the names they chose were fanciful, like Xanadu and Paradise River, but some reflected the stakeholders' pride in their background or former homes. The result was a curious reshuffling of Earth geography. Seminole, Roma, Milan, and Thessaly were a few such names.

The plateau behind Mount Garben was simply called Landing, but upriver from it was Cambridge-on-Jordan, the stakehold of the chief legist, Cabot Carter, who had been raised a Boston Brahmin on Earth. Drake Bonneau won a vigorous campaign to have the great lake he had discovered named for him. Three rivers led north from Drakes Lake, a stakehold he shared with several other miners and metallurgists.

Karachi Camp, named for an ancient city in Pakistan on Earth, was the chief mining stake, which yielded high-grade iron, copper, silver, mercury, lead, and vanadium ore. Key Largo, Monaco Bay, and Oslo Harbor were fishing centers. The dolphineers set up operations in Monaco Bay, near the main fishery and cannery. The seagoing ships, carried unnumbered pieces aboard the Yokohama and reconstructed in the new harbors, were made of siliplex, a light, almost indestructible compound. As it emptied of personnel, Landing still remained the administrative center and supply depot. The main animal-breeding labs were there, as were the hospital, training center, and school.

The nomads were assigned lands, though none of them intended to settle under roofs. Their lands were warm enough to allow them to sleep rough if they chose. Otherwise, natural shelter in the form of caves and cliff overhangs abounded throughout the varied landscape.

For a long time the wanderers were suspicious, expecting at every turn to be told to move on from their assigned territories. Although education was offered free to those who wanted to learn the trades, most of the traveling folk fought against even those loose conventions and vanished into the countryside, never to be seen again. Most of them were killed in the first Threadfall. Those who survived were brought to the north in the transports and, still defying conformity, became the nucleus of the Holdless people of Pern.

Until the eighth year of the colony, the stakeholds prospered.

The Dragonriders of Pern ® is a registered trademark.